Willower: Rewriting Life After Unimaginable Loss was released October 2023. It was hard to finally let go and send my story, which I’d kept hidden for so many years, out into the world. I hope it lands wherever it’s needed most and helps those searching for a story like this to feel less alone in their grief.

I want to say how grateful I am to have worked with Marion Roach Smith, the memoir writing coach who encouraged me and pushed me toward the finish line. And Jessica Hatch, the copy editor who helped me to cross that finish line. I’ve learned so much from both of these brilliant women.

And now: I’m excited to share with you an entire chapter sample—the book’s opening pages: about survival. For more chapter previews, go here.

A little backstory: this unnumbered chapter contains a favorite scene of mine: a bedtime story. Over the years, I’ve struggled to find a place for it. But the bedtime story didn’t seem to fit anywhere. I know, I know, William Faulkner said “in writing you must kill all your darlings.” I just couldn’t delete this darling. And then one day, I realized this misfit, my favorite scene, was starting to morph into the story’s setup. So . . . I decided to begin with it, and show you, the reader, right up front, who we were; what I had; and what I feared most.

about survival

Over the last winter break, one night at bedtime, the boys—Joey, six, and Sam, eight—wanted me to read an “action story” to them.

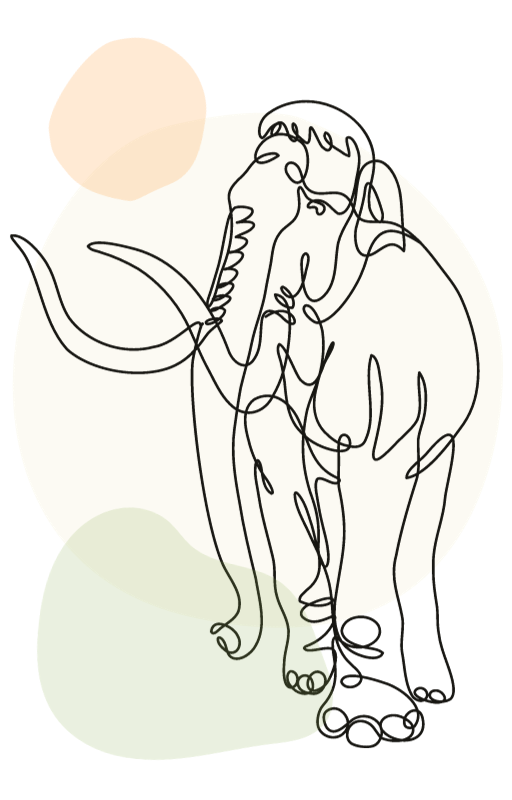

I sat on the edge of Joey’s bed with The Mammoth Hunters, from Jean Auel’s Earth’s Children series, and flipped to the page I’d bookmarked. Wrapped in his colorful blanket, Joey climbed into bed, snuggled beside me, and blinked at the mammoth-sized book. “How many pages is that?”

“A whole lot.” I grinned. “Did you go pee?”

“He did,” Sam confirmed as he curled up with his pillow and blanket on the floor. Sam was “too old” for “bedtime stories” and usually read on his own, but this night, since I was reading an action story about mammoth hunters, he joined Joey and me.

While Reggie the Chihuahua nuzzled into the bend of Sam’s knees, I picked an age-appropriate but action-packed hunting scene and got right into it.

It was the character Ayla’s first mammoth hunt. With only spears, how would she and her clan, so small and weak, take down the largest creature that walked the land? They’d use their strengths: intelligence, experience, and cunning. The hunters dashed toward the tusked beasts. They waved their smoky, movable flames, and shouted at the huge, shaggy, reddish-brown giants. The mammoth matriarch trumpeted warning cries. The herd was careening toward danger, stampeding into a gorge. Their screams blared and echoed off the icy rock walls.

Gripping their colorful blankets, the boys peered at me over their fingers.

“Too scary?” I asked. They shook their heads. “You want me to go on?” They nodded.

A young man threw a spear piercing the old she-mammoth’s tough hide. A second spear was thrown, lodging deep in her belly.

Joey never made it through even minutes of story time. His eyes were heavy and fluttering within sentences. Sam and I giggled and held up our fingers, referees counting down a semiconscious boxer: “. . . four, three, two, one.” Joey’s eyes closed, and Sam and I signaled to each other that the match was over, whispering, “He’s out!”

Sam settled back into his pillow and smiled. “I love you, Mommy.”

“And I love you. Tired?”

He shook his head.

Reggie gave an old man’s sigh, and Sam giggled. “Mommy, did you hear him? My little dude. That’s my boy. Yes, you are! Yes, you are!”

Reggie reciprocated, tapping his tail, smiling. Yes, I am. Yes, I am.

Sam’s eyes drifted back to the book, so I continued reading over Joey’s, and Reggie’s, deep breathing.

The old matriarch sank to her knees slowly, gracefully, valiantly. Praising her courage, a clan member touched the gallant old cow with his spear and thanked the Great Earth Mother for this sacrifice that would help Earth’s Children to survive.

I closed the book. “That’s enough for tonight. Let’s get you to bed.”

“Mommy, those hunters really cared about that mammoth, didn’t they?”

“They sure did.” I guided him to his room.

“And they cared about the Earth, too, didn’t they?”

“Definitely.” I tucked him in and kissed him good night. “Your lips are chapped, baby. Use your ChapStick.” I touched his warm cheek. “Go to sleep now.”

He reached for his cherry balm. On the nightstand, leaning against the lamp, his G. I. Joe action figure, Duke, was standing guard. Eyes open, alert, he never slept.

“Good night, Mommy. I’ll see you in the morning.”

“See you in the morning, brave hunter.” I went to the door and turned back to look at him. Nestled in, he kissed the air with waxy, rose lips and blew from his hand out toward me. I told him again, “I love you.”

“I’ll see you in the morning,” he assured me.

“See you in the morning,” I said once more before turning to leave.

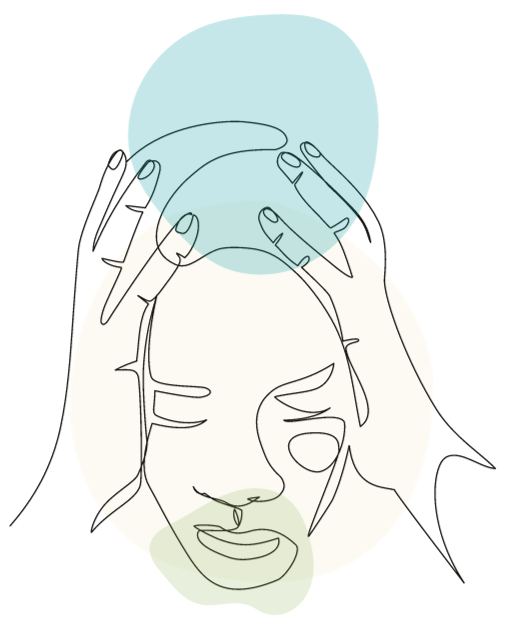

Through the night, when we were apart, it was the silence I feared most.

I finished devouring Jean Auel’s Earth’s Children series—the story of an orphaned girl, Ayla, and her life’s journey during the time when Cro-Magnons and Neanderthals coexisted—three weeks before Sam’s funeral. It had taken exactly forty-five weeks, according to my library records, to read those five mammoth-sized books. Those novels became my real-life survival guides.

For almost a year, I walked beside Ayla, my mentor. I hunted with her, raised a wolf cub, and ingrained in my mind her lessons on survival, perseverance, and aloneness.

I watched her care for Rydag, the boy she knew, with her trained medicine woman’s eye, had a problem with the strong muscle in his chest that pulsed and pushed blood through the body. Like my Sam, Rydag was slight and fair with soft, curly hair, a gentle sense of humor, and wise eyes. Also, like Sam, he couldn’t run as fast as the other children or play rough-and-tumble games.

And I committed to memory Ayla’s gestures, the way she performed at Rydag’s funeral ceremony as fine, volcanic ash rained down on us.

I tried to embody her strength and courage and wisdom—even her wardrobe. I wore a corduroy jacket the color of deerskin. Its faux-fur collar resembled an ermine’s winter coat. I toted a cross-body messenger-style bag, a rough, textured thing with leather cords hanging from its sides, so my hands were free to hunt and gather. This prehistoric costume made me feel stronger. It kept me in character: a strong leader, mother, hunter, and healer. Plus, I had modern medicine on my side, and health insurance, and less stress than Ayla had thirty thousand years ago. There were no animals hunting my children while they slept . . . or were there?

I tried to be vigilant, always ready, a predator and not prey.

But despite my vigilance and perseverance and modern medicine, death, as swift and cunning as a cave lion, snatched my beautiful boy and took him away. Today, I no longer wear the costume with the cross-body messenger bag. I’m not as strong as I was then, when I was in Cro-Magnon character. But I’m here, still, wandering between worlds, carving what I have seen (or imagined) on the wall of my cave. Like Ayla, I’m a survivor, one of Earth’s Children, hunting and gathering and soldiering on through the silence.

This is what I know now: Readjusting to living without our deceased children (though we are never detached from them) is an ongoing, unpredictable, and lifelong relearning process. There is no final goodbye, no recovery or end, only rewriting our stories, the ones we tell ourselves so that we can keep going, so that we can try to make the silence mean something.

When people say, “I can’t imagine,” about the death of a child, living with such loss, I want to say, “I can only imagine. It’s how I live with the unimaginable.”

Don’t get me wrong. Some days, still, the sadness swallows me up and I don’t want to pretend any longer, or write, or go on without my beautiful boy. And that’s when his voice comes through the loudest.

Mommy, I’m here . . . Don’t give up!

Continue sampling other chapters here: Table of Contents.

Willower is available now on Amazon, or wherever you buy your books. For more links, jump to my Book Page.

Let’s connect. Scroll a little further and leave me a comment and/or subscribe below.

(Your email address will not be published.)